Assignment: Compose an analytical essay about your experiences in this first semester of college. What might these courses help you do in your future?

Draft One-Nov 8, 2013

I am not taking any class this semester other than this English 111. But I am teaching three, and learning something different from each one and, about the experience of teaching three classes and taking one. The first thing I am learning is that there is never a day, when I am taking or teaching a class, that I don’t want the day to be over before it starts.

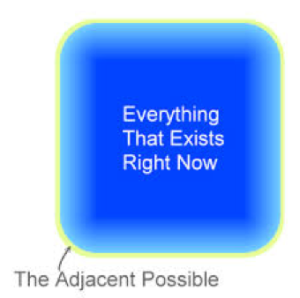

That is because teaching, for me, is about performing some kind of enthusiasm for a subject. And I am increasingly suspicious of my subject. I constantly ask myself, as a scholar and reader, the question that propels this writing assignment: “What will this subject yield in the future?”I confess that I don’t know what students will do with “The Novel” or “Basic Writing” or “Cultural Studies” in the future, because the future feels foreign to me, in the way that it didn’t when I was a student. It feels at once so new—robots, globalization, cyber-reality—and so sure of itself—we will know everything soon. Insisting to students that they are learning something from the word of the mind, from literature and intellectual discourse is, well, challenging. Insisting that they, or I, connect to (or confine to) a version of “success” is also problematic.

Perhaps that is what propelled me into this profession to begin with; I thought of knowledge, literature, and culture as ambiguous, what we used to call in the 1990s, a “construct” created by some hegemonic discursive power (I think that’s a direct crib from Foucault). My “profession”—my subject—is, largely, the “professoriate”—academia, and more specifically, the study and teaching of language, literature, and rhetoric. That definition, is itself emblematic of the way my subject matter resists the definitive. Question: “What have you learned from taking this course in writing, in the novel, in literary theory?” Answer: that we need to continuously re-evaluate what we are learning based on what we read, who we encounter, what history does to selves and societies.

But ours is the age of the definitive. The “Common Core” and CUNY’s “Pathways” and the “Race to the Top” culture demands defined success. And I think it is more than my own mid-life crisis (did I mention I am taking a freshman composition course?) that makes me question what the study of literature and writing will mean as data and determined rubrics for skills take over the economy and education.

And so, back to the beginning: I am enrolled in first-year composition because I am looking forward to figuring out what to do in this age of transition. And writing seems one way to find out.

Draft Two

Can the Future be an Outcome?

There used to be two versions of the college course syllabus. There was the one the professor gave to the students and the one she kept in her head, or in her drawer, or in a file. The students’ version, the “official” or public copy had all the usual information needed to navigate the class from week one to week fourteen: dates organized by weeks, readings due, assignments and their deadlines, and policies—the “I won’t accept late papers” or “Midterm counts for 30% of the final grade” or “Office hours Tuesdays from 11:15-11:40”—type of policies. I’ve received dozens of these syllabi over the course of four years in college and five as a graduate student; I’ve given out as many since becoming a professor of English in 2000. The purpose for these documents was to map at the trajectory of the course; the purpose of the courses was presented as more of a promise: show up and fulfill the requirements of the syllabus and the meaning of the class for you, for your studies, indeed for your future would be revealed.

But as the economic downturn, globalization, the ubiquity of digital media, the changing geopolitical power structures of nations becomes the norm, “the future” and what will count as meaningful and important for success in it, is increasingly unknown and complex. At the height of uncertainty, scarcity of resources and technological and cultural complexity comes a new kind of syllabus: the outcomes statement syllabus. This essay explores the relationship between the courses I teach—humanities seminars and beginning writing classes—and these new syllabi. I find the relationship vexed and ambiguous. Here I attempt to work through some of the thorny issues of that connection and to consider whether the new college syllabi—and, presumably, more outcomes-oriented college courses—can lead to a “successful future.”

In the outcomes syllabus, a professor includes the learning goals for the course and how these goals will be measured, through assignments, feedback, and, ultimately, rubrics that offer a grade. The simplest and, to my mind most accurate, definition of “outcomes statements” comes from Christopher Gallagher, a professor of writing: “statements identifying what students will know or be able to do at the end of an activity, unit of instruction, course, or program of study” (44). Google “syllabus” in courses ranging from Physics to Philosophy and you’ll find these statements, especially from public colleges and universities, where they have been mandated with more oversight than the private, liberal arts institutions Outcomes statements can be very rigorously specific or aspirational and vague vague, like my own.

In the early years of the 2000s, American colleges and universities began mandating these statements in college syllabi. A recent report published by the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education offers a brief history of the studies leading to this decision. The dominating question of In an age when what counts as knowledge is shifting and since 2008 especially, when job loss and global economic crises change the funding for and priority in educational investment, outcomes have become one answer to the question “What is College For?” and more specifically, “What Will College Do for Me in the Future?”

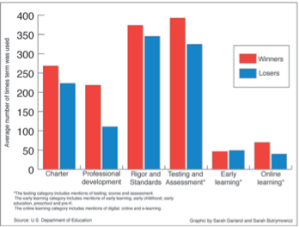

In their widely cited polemic Academically Adrift Richard Arum and Josiah Roska join the ever-increasing chorus of naysayers who believe that colleges should be held accountable to better, higher, more accurate standards. Since the publication of that book in 2011and in concert with an ever-growing concern about government “entitlement” spending, assessment in general and outcome statements in particular has become a kind of panacea for a new education crisis. The last few years (2010-2013) have been particularly active for the Obama administration, which aims to explicitly link federal funding to measurable results of college-wide and course specific outcomes statements, as this recent Inside Higher Ed article explains.

Traditional humanities courses, where students learn “critical thinking” and practice reading and writing in ever-increasing complex ways offer a challenge to the outcomes culture. These courses, which marry skills acquisition (writing effectively) with idea-generation (reading critically), have many outcomes but not as many ways to measure them. It’s not that you can’t measure whether or not a student has read particular books or can write cogently about them. You can. Professors and high-stakes testing and essay exams do all the time, with varying degrees of uniformity. The challenge the humanities bring to outcomes involves something else. Having satisfied all the learning goals of a course on, say, “The Novel” or “English Composition” or “Literary and Cultural Studies in the 1990s” (three courses I am teaching this semester) professors and students will still not be sure if those skills or “habits of mind” as we in the humanities like to say, will be obviously connected to “the future.” That is, if the future means what the Obama administration is calling the “new” jobs of the “twenty-first century.”

In my own scholarly field, Composition and Rhetoric, there is an entire new sub-discipline emerging called that studies what one important article calls “The Question of Transfer.” Scholars in this area of writing and rhetoric seek to find the cognitive and rhetorical links, the proven reciprocity, between beginning writing courses and advanced “discipline-specific” courses that happen later in college. Some important data about writing and “reflection” and reading and advanced critical thinking have been made. But these findings won’t get to the question that drives this essay—the relationship between outcomes and obtaining “future success.”

Christopher Gallagher, the scholar whose definition I cited earlier, makes an important case for rethinking “outcomes.” Outcomes can become useful, he argues, not as end-statements but if they focus more on the means of individual learning connected to larger programmatic goals. Gallagher’s article “The Trouble with Outcomes: Pragmatic Inquiry and Educational Aims” uses philosophical Pragmatism as his way into this critique of outcomes statements. But his suggestion that we focus not on outcomes but on “articulation” between individual and larger goals, while enormously important, again doesn’t satisfy the quest for “future success.” That’s because (?) outcomes assume that a future filled with success is known, attainable, and desirable. Now I don’t mean to suggest that humanities scholars are nihilists who seek apocalyptic tomorrows. Rather I want to suggest that one of the most important purposes for college humanities courses is to question what I or you or “we” mean by “future.”

Some of us are having trouble (or, more accurately are troubled) by “outcomes statements” not because we don’t know what we are learning, or can’t measure it, or don’t believe in it. It’s because we don’t know what the “future” should be, or mean, or do. We never really have. Anyone who has ever tried to document reality in writing, or tried to come back to reality after being undone by fiction, or attempted to make connections between self and society, and between history and experience, and between the forces of political and social construction and the potential of collaboration and innovation understands that “future success” needs not only to be accessed but analyzed. Courses in reading and writing question versions of, and syllabi for, success, future, past, and present. And that sounds pretty difficult to measure (accurately and in a way that is standardized across courses, not only at an institutional level, but at the level of American undergraduate education).

In the last year, recognition that the outcomes culture of my profession—the academy—and my chosen subject of study—the humanities—may be ad odds, or at least at a crossroads, propelled me back to the classroom. Not to teach or to make statements or even to critique, but to experience. That is, to experience what it’s like to encounter the requirements of a course in writing and reading while living in this age of outcomes. And so I am in my second semester as a student of English 111, the first semester of freshman composition required at the college where I normally teach. There is a syllabus for this course, with the mandated outcomes statements. So far, just past the mid-point of the term, the professor and most of us students, are living up to those outcomes. And our collective ability to do so has quelled some of my anxiety. But it has also introduced a different worry. What happens when reading and writing can conform to a recognizable version of a future? I suppose that is the subject for the next freshman composition assignment.

a) assess where each student is and wants to be as writers and readers

b) allow each student to be comfortable with and proficient in writing in response to academic and journalistic texts

c) allow each student to be comfortable with and proficient in writing academic and short-form web-based essays that cite other texts

d) allow each student to be comfortable with and proficient in researching and responding to academic and popular webtexts

e) allow each student to be comfortable with and proficient in understanding the appropriate rhetorical mode, audience, and language choices for writing tasks

f) create a community of writers where each class member engages respectfully and critically with each other and with course material.

These goals correspond to the following goals created by the English Department at Lehman College. Students at the end of a 100-level writing course should be able to: compose a well-constructed essay that develops a clearly defined claim of interpretation which is supported by close textual reading; employ effective rhetorical strategies in order to persuasively present ideas and perspectives; utilize terminology, critical methods, and various lenses of interpretation in her/his writing; apply the rules of English grammar; adhere to the formatting and documenting conventions of our discipline.