Welcome (back?) after a long hiatus. My first post for the 2014 academic year was published on another site–the AEPL blog: The Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning–thanks for the opportunity.

Perpetual September: On Being a Beginner in an Age of Complexity

September is the most muddled of months: a mix of summer and fall, of shorter days and longer commitments, of anticipation laced with last year’s losses.

And then school starts.

The rituals of a new term—the schedules and expectations and first impressions—should by now be old hat. Over a decade of teaching and writing and almost the same for parenting means that I can update syllabi, reuse supplies, even trust that I’ll finish that essay’s last draft. Still, every start of the year reminds me of the persistent challenge and delayed rewards of starting over.

Beginnings are always hard. But in the last few years it seems like Septembers are getting more challenging. The digital revolution asks anew how we are to survive and thrive in a society becoming more competitive and complex by the moment. And education seems to be a focal point for our anxiety. We’re a “race to the top nation”; everyone can and should be ahead of their time.

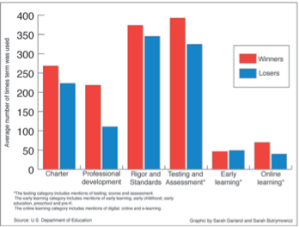

Over the last half-decade countless colleges and universities are revisiting their general education curricula, updating them to meet perceived needs of a culture that needs results, not rookies. A host of recently passed federally mandated and state standards at the K-12 and college level confirm this view by defining the purpose of courses by their measurable endgames—by how they prepare students for a certain and useful future. The result has been mass cutting of introductory courses: of time spent adjusting to the beginning. “Come the Revolution” writes New York Times opinion writer Thomas Friedman ushering in a debate about a new kind of education for a generation of “mastery.” Knowledge needs to be tailored, networked, global, and, above all else, determined by its outcomes.

“Make your point first, write your introduction last” I instruct my first-year composition students, trying to rescue them from the snare of endless first sentences and the pitfalls of missed deadlines. I say this year after year. Yet the truth is that introductions rarely just find themselves fully formed at the end of the page, ripe for mere cutting and pasting. Like everything about the writing process, they happen painstakingly and haphazardly. By my fifth draft I can’t say what paragraph came first or last. I only know (and barely) when I have to let that piece go because another one awaits.

Beginning permeates everything, especially in education. Each new semester and class and every first paragraph feels like learning again how to breathe. The process is natural and excruciating all at once.

But maybe that’s how it’s supposed to be.

Last September, as my institution inaugurated its updated curriculum for this complex age, I decided to do some research on the role of starting out in a culture of finishers. And it turns out that beginners—deep, critical, curious, fearless and fearful minds embarking on the unknown—are critical to a transforming world.

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” The opening line to Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki suggests that seeking complexity by cultivating mastery clutters clarity and truth.

This book’s rigorous instructions on meditating insist that advanced understanding requires concentrated work at recognizing what’s really in front of us, not just what lies ahead. Being a beginner in the Zen tradition is not a disease to be inoculated from with specialized study. Rather it’s the endpoint of accessing wisdom, and complexity.

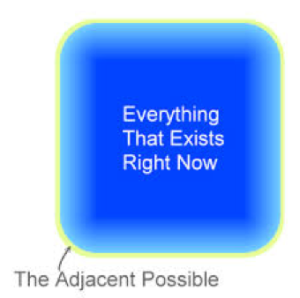

Through his research on cell reproduction, the American Biologist Stuart Kauffman comes to a remarkably similar conclusion. “Something has obviously happened in the past 4.8 billion years,” he writes in his book Investigations. “The biosphere has expanded, indeed, more or less persistently exploded into the ever-expanding adjacent possible.” His observations of living and social systems reveal a universe that is evolving differently than before: towards more complexity. But in order to sustain this move towards more complexity we need a constant supply of new beginnings, what Kauffman defines as not-fully evolved life-forms of the “adjacent possible.”

The “adjacent possible” represents those structures in the universe that are at the start of their development. They have not yet combined with other structures, what Kauffman calls the “actuals” of the universe. But they are moving towards evolution. He calls these structures “almost actuals.” Without them, complexity stagnates.

Blame it on science. Or meditation. Or middle age almost upon me. Whatever the reason, I’m starting to appreciate that moving on—to the next page, the new class, October—can’t happen without this perpetual starting over. In a culture that functions as if it’s always the blooming season of spring, I’ll stick with September.